Chalkboard to Banana Resort, story of Abel Morang’a

Written by Nyachae Brian on September 29, 2025

Early Life and education

Abel Morang’a was born in 1960 at Riangabi Sublocation, Kerera Location, Ibeno Ward, Nyaribari Chache Constituency, Kisii County. He is the firstborn in a family of two, son to the late Samson Nyamwega and Eunice Moraa. Their mother passed away when Abel was three years old, leaving him and his younger brother, Reverend Daniel Nyamwega, then six months old, as orphans.

Abel enrolled in primary school in 1967 at Nyamagwa, where he sat for his CPE (Certificate of Primary Education) in the same year.

“Life while in primary was not easy. My school was 2 kilometers away from home, and I would walk barefoot to and from school. Sometimes we missed lunch,” narrates Abel.

His father, an agricultural extension officer, later married two more wives who helped take care of Abel and his brother. During that time, most people had embraced education.

“School was incorporated with work. You had to harvest a bucket of pyrethrum daily before you ate. We also played football among other childhood games,” recalls Abel.

In 1978, he sat for his O-levels at Nyamagwa Secondary. He later enrolled at Kisii Progressive High School (a private school) before transferring to Itibo High School for A-levels, where he finished with Division 3 in 1978.

“Life was not easy at Itibo. We had to fetch water down a cliff and persevere drinking porridge and eating githeri,” he recalls.

He fondly remembers teachers who mentored him; David Monda Omesa (History and Kiswahili), Livingstone Anyona (CRE) at Nyamagwa Secondary, and Jason Amati, the principal at Itibo.

“Amati was a disciplinarian. He only showed up in school on Monday or Friday but had a list of all students who had misbehaved during the week,” recalls Abel.

He says the principal gave him early lessons in leadership, particularly the need for strong management systems.

First job

Due to financial constraints, Abel could not advance further. His father encouraged him to seek employment.

While in high school, Abel aspired to become a police officer but failed the recruitment test because of flat feet and short stature.

In 1979, he went to Nairobi, where his Uncle Sam Nyambweke referred him to someone who secured his first job as a casual laborer.

“I carried heavy sacks for three days, earning Sh20 per day without lunch. On the third day, I quit the job,” explains Abel.

He bought a red shirt with the Sh60 he earned to remind him of the hardship. Today, he estimates an equivalent shirt would cost Ksh2, 000.

Living in Kangemi at the time, he boarded Kenya Bus at 50 cents to work. To save fare, he often alighted at Westlands and walked the rest of the way.

After quitting, he returned home, got a share of land from his father, and began planting pyrethrum.

“My dad was disappointed. He had taken me to school, only for me to return home to farm,” Abel recalls.

Untrained teacher in Kitui

His cousin, who worked at a creamery in Kisii, informed him about a teachers’ recruitment drive. After four months of waiting, Abel was hired as an untrained teacher at Yoonye Primary in Kitui in 1980.

He recalls being accommodated by a stranger he met on the bus to Kitui. The next day, while at a hotel in town, he met a former classmate who helped him settle.

“Kitui was indeed a hardship area. It was the first time I saw maize porridge and black tea sold in a hotel.”

That year, Kenya experienced severe famine. Yellow maize—cattle feed in America—was donated to Kenyans.

“Government officers outside Kitui were prioritized for the donation, which favored me,” explains Abel.

Despite hardship, pupils often supplied him with mangoes and papaws. He worked for seven months without pay, but was eventually paid in lump sum.

“Occasionally, I would receive maize, beans, and flour from home sent via Akamba Bus. It usually arrived after one month,” he narrates.

Only two buses operated in Kitui then: Mrembo and Malaika, each making one trip daily—one to Mombasa and the other to Nairobi.

Thogoto teachers training college in Kiambu

Later, Abel successfully joined Thogoto Teachers Training College in June 1981 after passing the interview. His name was published in the Daily Nation.

“Fees was Sh680 for the two years, and I paid from my salary,” he recalls. He earned Sh665 per month.

At college, each student received two uniforms, textbooks, notebooks, foolscaps, a bar of soap, and four tissue papers monthly. His cohort was the first and last to receive a stipend of Sh200 per month.

Traveling then was affordable. “In 1981, boarding Kenya Bus from Kikuyu to Nairobi cost 50 cents. From my stipend, I spared Sh1 every weekend to visit friends in Nairobi until 1983, when I graduated,” he recalls.

1982 Coup Attempt

Abel first heard about the coup through a radio he bought with his Kitui salary.

“I was in the dormitory when Leonard Mbotela announced that ‘all political prisoners, including Anyona, be set free, and the police be ordinary citizens.’ I loved Anyona and disliked police officers for their brutality,” Abel recalls.

He informed fellow students, being the only one with a radio. Later that day, however, the presenter announced that normalcy had been restored

“The presenter said: askari waaminifu wamefagia wale vinyangarika wote. Moi ndiye anasalia rais. That scared me because of my earlier reactions,” he explains.

Teaching Career

Despite a government directive that all graduating teachers be posted in their home districts, Abel defied it. He listed Kericho and Narok as first and second choices, Kisii as third.

He received his placement letter immediately after his final exam and was posted to Chinchilla Primary in Kericho March 1983.

Abel’s teaching career began in 1983 and spanned over three decades, marked by both remarkable achievements and significant challenges.

Schools he taught at as a trained teacher:

- March 1983 – Chinchilla Primary (for one week)

- 1983–1984 – Kerenget Primary in Kericho (one year)

- May 1985–1988 – Sondu Primary

- 1988–1992 – Ibeno COG Primary

- 1992–1995 – Nyamagwa SDA Primary (two and a half years)

- 1995–1997 – Rikendo Primary

- 1997–2001 – Riangabi Primary

- 2001–2004 – Kisii Primary

- 2004–2018 – KARI Primary, where he took early retirement

Teaching experience

Immediately after reporting to his first school, Abel clashed with the head-teacher, who demeaned other teachers. Abel openly challenged him, which made the head-teacher gloomy for a whole week. The following week, Abel sought a transfer from the education office.

At Kerenget Primary, after one term, the head-teacher (a P2) was transferred, leaving Abel—the only P1 teacher—as acting head-teacher. He managed three other teachers, and the school offered classes up to Standard 4.

In December 1984, Abel married, prompting him to seek a transfer.

“While in college, the first Attorney General of Kenya, Charles Njonjo, married at the age of 52. That challenged me. I decided to marry young so that by the time I reached retirement age, I would be done educating my children,” explains Abel.

At Sondu Primary, Abel became deputy head-teacher. As an agriculture teacher, he mobilized pupils to plant maize. After harvesting, he used the proceeds to buy football, netball, volleyball, nets, chairs, and reference books for teachers. The remaining funds were reinvested in fertilizer and seedlings.

This initiative led to conflict with the head-teacher, who accused him of insubordination. The education office investigated, confirmed Abel was right, and faulted the head-teacher. Abel still sought a transfer, which was granted after two months.

At Rikendo Primary, Abel transformed the school from the lowest performing in the district in 1995 to the most improved within a year.

“I found ways to motivate teachers and learners. The next year we received a trophy as the most improved school,” he recalls.

However, community politics soon emerged, as some parents preferred their own committee. During an annual general meeting, Abel received news of his in-law’s death in an accident near Elementaita. When he returned, parents had elected a new committee. Realizing he would not make progress, he applied for a transfer to Riangabi Primary.

In 1996, Abel was elected Assistant Treasurer of the Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) Kisii branch. Despite his union duties, he ensured he was in class by 6 a.m. and taught until 10 a.m. before attending to union matters.

However, locals began politicizing his work, accusing him of neglecting teaching. Some, who had been his schoolmates but were less successful, envied him. Political divisions worsened matters—most locals supported Simeon Nyachae, while Abel was perceived to lean towards Prof. Sam Ongeri, the two being political rivals.

At one point, the situation forced Abel to quit teaching and headship for three months, focusing on farming. Education officers later persuaded him to return, transferring him to Kisii Primary.

At Kisii Primary, Abel spearheaded major improvements, giving the school a facelift. However, the District Officer colluded with another teacher to have him transferred. Abel refused, resigning as head-teacher but agreeing to remain as an assistant teacher.

In 2004, he was transferred to KARI Primary, a newly established school with only Classes 1 to three.

“We laid strategies that saw the school become an academic champion in the region. The head-teacher, Mr. James Ndubi, was very understanding. Together, we collaborated well,” narrates Abel.

All teachers agreed to transfer their children to KARI from boarding schools, both as a sign of confidence and as motivation to give their best.

“Because of my dedication to learners, God blessed my children too. I am a father of two sons and two daughters. My lastborn graduated when I was 53 years old,” he says.

In 2018, after educating all his children, Abel took early retirement.https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/chalkboard-banana-resort-story-abel-moranga-egetuori-africa-v6xmf

Entrepreneurship – Banana Resort

John Oigara, then owner of Kisii Hotel, inspired Abel to start a resort where he could host friends after retirement.

He began with a small shop near Gulf Energy petrol station in Nyosia. Later, he leased nearby land and in January 2017, started Banana Resort.

“I began by planting 140 bananas, which I envisioned would pay my workers before the business thrived,” he recalls.

The resort opened in October 2019, just before COVID-19 struck. Despite the pandemic, he survived financially thanks to banana farming.

Today, Banana Resort is a legacy project, offering catering, accommodation, and conference facilities to people from across the country.

Character traits for leadership

Abel believes leaders must be good listeners, role models, and change-makers.

“All through my career I copied good practices from others. For instance, I have never bought milk since 1990, having emulated my father by keeping my own cattle,” he says.

His career taught him firmness, punctuality, and responsibility. He urges young people not to despise job opportunities and calls on parents to instill responsibility in their children.

“Parents should challenge their children to be responsible. Let us not babysit them,” says Abel.

Reflecting on his life, he expresses contentment:

“All my dreams have been achieved. In this life, you don’t need so much money—just enough to feed yourself, move around, and have shelter,” he advises.

Apart from Banana Resort, Abel takes pride in the countless children he shaped as a teacher.

His rallying call remains:

“Do good to people at any time, wherever you are.”

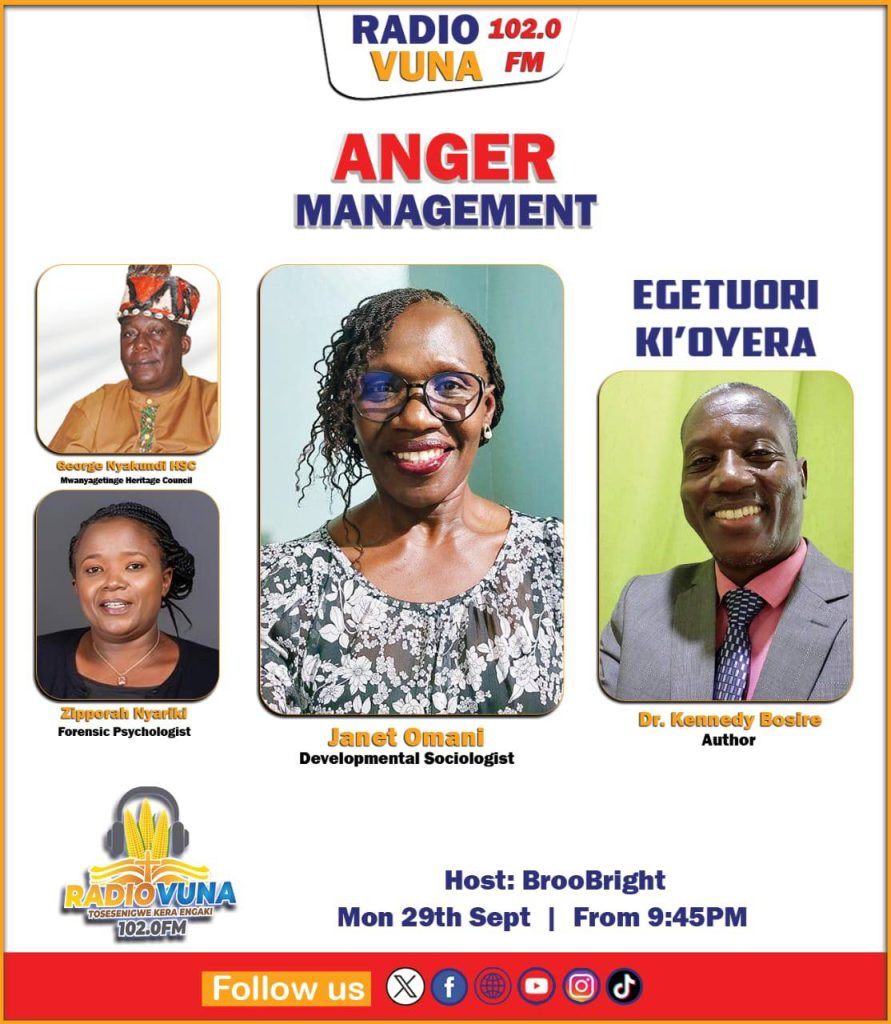

Head of Radio|Media Programming Expert|Broadcasting & Journalism|Virtual Assistant|Radio Vuna